Available from Cedille Records

Audiophile Audition

By Gary Lemco

May 26, 2014

original

link

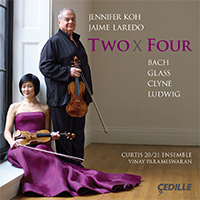

Jennifer Koh extends her hegemony in violin matters contemporary by teaming with mentor Jaime Laredo in homage of the two-violin concerto ensemble.

The idea of Two X Four (rec. 12-17 March 2013)sweetly attests to the commitment of violinist Jennifer Koh and her teacher-colleague Jaime Laredo to present four two-violin concertos – including two world premieres – by diverse composers, using Bach as an archetype for the form and extending an invitation to contemporary composers to add concertante works to the repertory. The Philip Glass piece Echorus (1995) already pre-existed, as a testament to the late Yehudi Menuhin and his own protégé, Edna Mitchell. Menuhin and Mitchell had commissioned fifteen composers to craft pieces meant to celebrate the theme of human compassion.

The opening Bach Concerto for Two Violins enjoys its customary good fellowship of expression, with brisk tempos and a palpable affection’s emanating from the violin principals. The Curtis Institute students and alumni provide a rich, frothy texture for the tutti sections. The 12/8 Largo conveys a special warmth of feeling, especially after the polyphonic pyrotechnics of the first movement’s four-part fugue. The lulling arpeggios and lilted echo effects never fail to suggest a partnership both intimate and exalted. An exciting canon, the final Allegro juxtaposes rapid figures with serene legato, the constant ritornellos having become a race or test of individual wills who magically share a common love of invention.

Anna Clyne (b. 1980), a Chicago Symphony Orchestra composer–in-residence, wrote Prince of Clouds (2012), her first concerto, while contemplating the idea of musical lineage passing from one generation to the next. Ms. Clyne sees this time-honored process as “a beautiful gift.” The New York Times called the one-movement Prince of Clouds “ravishing,” while the Chicago Tribune described it as “music one can listen to again and again and find new things to appreciate each time.” The piece casts a wistful, nostalgic atmosphere that might beckon to Barber and to Vaughan Williams. Its hectic, strikingly dissonant moments occur over pedal points that want to resolve themselves rather softly, traditionally. The ubiquitous pizzicatos from both the two soloists and the Curtis 20/21 Ensemble resonate with potent energy. The last four minutes suggest a mercurial folk dance and emergent hymn, alternately manic and lyrically dreamy.

Philip Glass (b. 1937), although most often designated as a “minimalist,” likes to conceive his music as “works with a repetitive structure.” Echorus proffers a seven-minute work that exploits echo-effects and what is meant to be a songlike character. Adherents will embrace Echorus as a characteristically attractive, hypnotic, undulating Glass score. It appears to “borrow” the main arpeggio from Bach’s C Major Prelude from WTC I and reiterate enough times so we can easily recall it. Whether pleasant euphemisms will remain with you for this exercise in refined monotony may subject your aesthetic jury to some debate.

A composer based at the Curtis Institute, David Ludwig (b. 1974) wrote his evocative Seasons Lost (2012) as a contemporary counterpart to Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, informed by his dire concerns about climate change. Mr. Ludwig’s four-movement, double-violin concerto is “full of beautiful ideas contrasting with playful/menacing Vivaldian gestures” (Philadelphia Inquirer). Ludwig’s progression moves from Winter through Fall, using at first open, modal chords, augmented scales, and pedal points. “Spring” evolves as a duet for the two principals, assisted by the string ensemble. Scales and repeated riffs in high registers dominate. The longest, “sultriest” movement, “Summer,” utilizes portamento and slides set in trio form to suggest “hazy, smoky nights and smoldering bonfires.” Whether the last pages represent some apocalyptic fire and its aftermath or not, the final bars proffer weepy consolation or melted objects from a Dali painting. “Fall” begins abuzz with “howling winds in autumn” set in quartet form. While some relief follows, it does so grudgingly, only to yield to the chilling effects of a ravaged balance of Nature. Sterling sonics from Engineer George Blood keep our ears pounding.

Copyright ©2014 Audiophile Audition