The New York Time

By Joshua Barone

April 9, 2022

original link

Two Musicians of Color Are Creating Their Own Space

“Everything Rises,” by the violinist Jennifer Koh and the singer Davóne Tines, mines their experiences in the white-dominated classical music field.

The violinist Jennifer Koh and the bass-baritone Davóne Tines collaborated on the performance project “Everything Rises,” which premieres April 12. Credit Victor Llorente for The New York Times

The violinist Jennifer Koh and the bass-baritone Davóne Tines collaborated on the performance project “Everything Rises,” which premieres April 12. Credit Victor Llorente for The New York TimesSeveral years ago, when the bass-baritone Davóne Tines was starring in Kaija Saariaho’s “Only the Sound Remains” at the Paris Opera, he stepped out of his dressing room and saw something surprising: another person of color.

It was the violinist Jennifer Koh, whom Saariaho had invited to see the show. Koh noticed the same thing. She, an American daughter of Korean refugees, and he, a Black American, were outliers in a crowd of white people. There was, Tines recalled, “a line of connection there that we had without really having met or talked.”

“I think that line of connection,” he added, “was the beginning of our relationship, which continued to deepen with the development of this piece.”

Tines was referring to “Everything Rises,” an hourlong work that he and Koh have been collaborating on since they met. It has been a project of evolution and introspection, changing even to respond to racialized violence against Black and Asian American people during the pandemic. Originally planned for spring 2020, it is now premiering on April 12 at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and traveling to Los Angeles later that week.

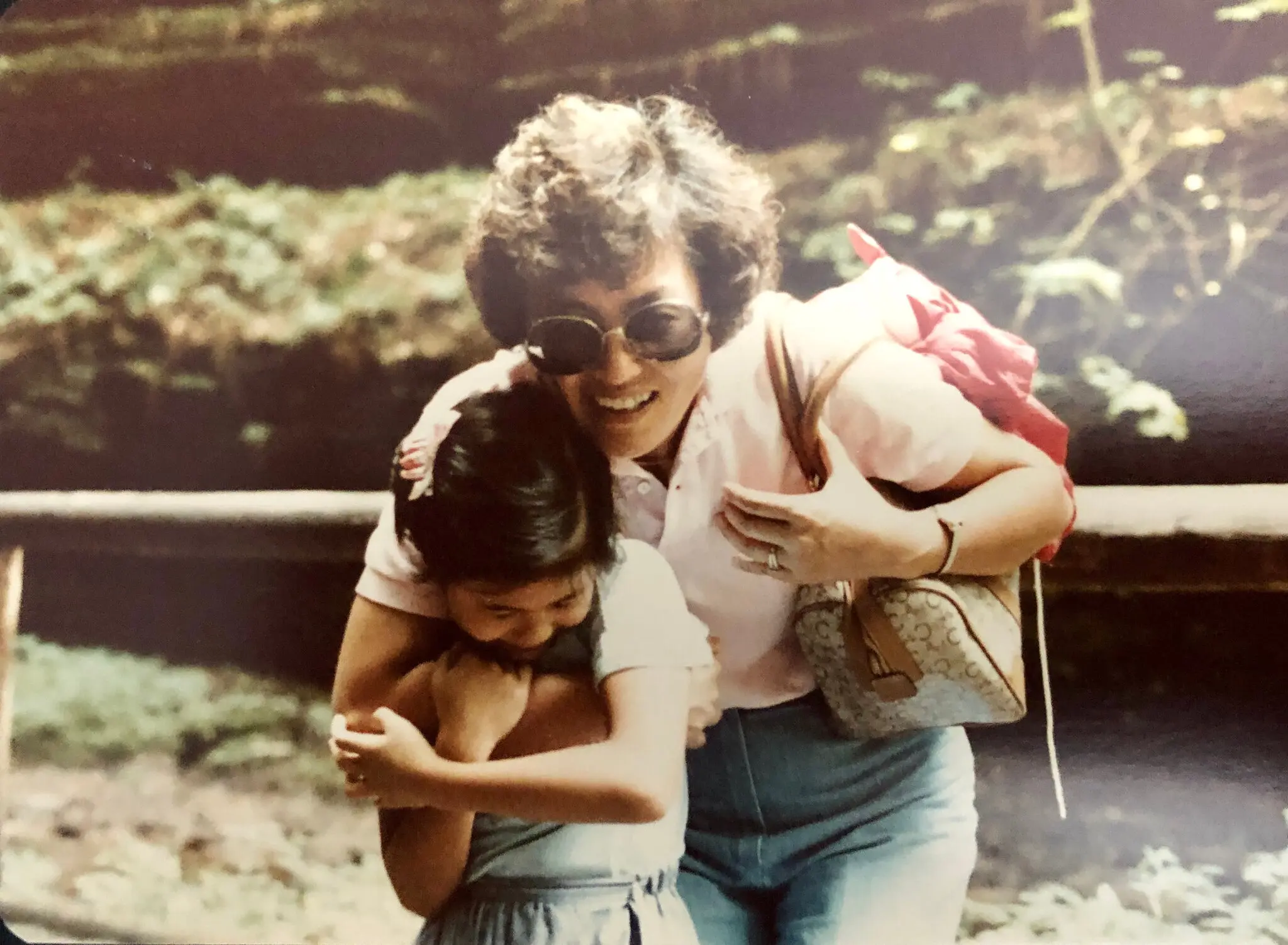

Difficult to categorize, “Everything Rises” is a multimedia show with elements of theater, as well as a documentary in music (composed by Ken Ueno) about Tines and Koh: their experiences as people of color in a predominantly white field, their journey toward honesty about themselves and their audiences, and their explorations of their families’ history. Along the way, they celebrate their maternal lineages — based on interviews with Tines’s grandmother, Alma Lee Gibbs Tines, and Koh’s mother, Gertrude Soonja Lee Koh — as they arrive at something like independence from the pressure of the music industry.

A young Koh with her mother, Gertrude Soonja Lee Koh, who was interviewed for part of the show’s libretto. Credit via Jennifer Koh

A young Koh with her mother, Gertrude Soonja Lee Koh, who was interviewed for part of the show’s libretto. Credit via Jennifer Koh“It’s about revealing who we are,” Koh, a recent Grammy Award winner for her album “Alone Together,” said over lunch with Tines. “Whenever you see someone walking down the street, there’s a whole life and a whole history that they carry with them that you might have no idea about.”

Getting to this place — what Tines called the richest possible form of “Everything Rises” — has taken years. The creative team has changed more than once; so has the title. An early workshop was called “The 38th Parallel,” and was more focused on the families of Koh and the composer Jean-Baptiste Barrière, who is Saariaho’s husband. He left the project over creative differences, and the shape began to gravitate toward one based on Tines and Koh’s relationship.

More collaborators came and went, but the final lineup — including Ueno, the dramaturg Kee-Yoon Nahm and, within the past half year, the director Alexander Gedeon — made for what Koh felt was the most comfortable environment yet. Almost everyone is a person of color, and “there’s something significant about that,” she said, “because there are experiences that are just understood.”

In the process, the project has become increasingly unflinching. “Since this piece is about gaining personal agency and revealing truth,” Tines said, “and since we are allowed the space to explore personal agency and truth, there is an opportunity to say things to audiences that we otherwise would never be given the space or encouragement to say.”

He continued: “We are conscious of who our audience traditionally is. Pandering to them would be ignoring what our realities actually are. We’re past the point of allowing the proscenium to be a wall. I don’t think there’s much gained by making what’s onstage a plastic representation of life.”

That belief guided decisions such as how to end the piece. At one point, Tines had planned to sing a gospel hymn, “The Lord Will Make a Way Somehow,” and segue into the beginning of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.” It was a way, he said, of showing “the dichotomy of being a classical singer in canon work, but also bringing my own personal and Black experience that fuels and informs everything I do.”

Alma Lee Gibbs Tines, Davóne Tines’s grandmother, with, from left: John H. Tines Jr., his uncle; Michelle Antoinette Tines-Spencer, his mother; and Sabrina Tines, his aunt. Credit via Davóne Tines

Alma Lee Gibbs Tines, Davóne Tines’s grandmother, with, from left: John H. Tines Jr., his uncle; Michelle Antoinette Tines-Spencer, his mother; and Sabrina Tines, his aunt. Credit via Davóne TinesAfter a run-through, Koh told him that she didn’t feel like it was right. But, he responded, it was his way of expressing balance and resilience. Then she said: “You know, you don’t have to give that to the audience. They haven’t earned that from you. You do not have to give them your ways of coping; that is for us to hold as our own safety.”

Her words made Tines cry. “I had never really framed it that way,” he recalled in the interview. “If I give this to an audience, is it giving them an out? Is it saying that my release is being offered as your pathway out of it as well? I realized I had been giving away the potency and agency of what I was trying to share by also allowing an escape hatch.”

“Everything Rises” now has an original score throughout, along with text taken from recorded conversations between Tines and Koh — in part, Tines said, “because it’s about sharing the truth of our experiences, instead of tying to aestheticize our experience. I don’t need to find a poem that represents something I can say more directly.”

Some material has been taken from elsewhere, especially the lyric for “Strange Fruit,” which is given a new setting near the end of the work. That sequence had a test run, in the form of a music video, last year as part of Carnegie Hall’s series “Voices of Hope.” In it, Koh’s playing — agitated extended technique — accompanies historical images of lynchings and racist cartoons.

Tines enters later with a somber, slow treatment of the text that gives way to something more beautiful, a showcase of his pillowy and soothing upper range that is at odds with contemporary videos and photos of violent attacks and bloodied faces. It’s gorgeous and unbearable — made even more difficult by the juxtapositions of female victims and Koh walking down a New York City sidewalk. But it ends with optimism: a message of togetherness, including from two girls, one Black and one Asian American, holding a sign that says, “This is what solidarity looks like.”

“‘Strange Fruit,’” Ueno said, “encapsulates so much of what the mission of the piece is about,” and noted that it came out not long after six women of Asian descent were murdered in Atlanta last year. (The video cites a rise in hate crimes against Asian Americans; in December, New York City’s Police Department reported a 361 percent increase in attacks targeting them compared with the previous year.)

The show isn’t all so intense, but it is unsparing in its discussions of race, history and classical music. Gedeon, the director, said: “It’s raw, it’s edgy in a way, and it’s haunting. The words are written with this very direct language in confronting the reality of experience of being person of color in this predominantly white space.”

“Hopefully what we’re doing in this work,” Koh said, “will open space for people of color to tell more truth.” Credit Victor Llorente for The New York Times

“Hopefully what we’re doing in this work,” Koh said, “will open space for people of color to tell more truth.” Credit Victor Llorente for The New York TimesIt begins with Koh and Tines dressed as they might be for any performance — her in a gown, him in tails — because, Tines said, “so many of our stories have come out of what it means to present oneself.” They intentionally fulfill stereotypes of concert dress, and from there interrogate audience perception and the extent to which they are complicit in that. In a song called “A Story of the Moth,” Tines sings:

I was the moth

lured your flame

I hated myself for needing you

dear rich people

money, access, fame

From there, they recount journeys of personal and historical discovery. Koh spent about 10 hours interviewing her mother, Soonja; Tines had already been secretly recording his grandmother for “quite some time.” Audio from those conversations is included, to revealing effect, such as Alma’s account of a lynching — “They killed him and hung him, cut his head off and kicked his head down the streets” — in poetic fragments woven with Soonja’s memories of violence in Korea: “So I saw people being tortured and people on the trees, bodies hanging on the trees.”

Ueno’s score — for the two performers and electronics — is an analogue to code switching, with faux classical and traditional Korean music, along with ’70s pop and contemporary avant-garde idioms. “It’s an allegory of their experience,” Ueno said, “but it’s also a way to highlight the broad virtuosity of what Davóne and Jenny can do, things like Davóne’s angelic high range and profundo low range, and Jenny’s extended technique.”

Gedeon said that because he came to the project so late, most of his work has been “massaging these pieces into a clear through line and creating more interstitial material that brings them on this journey of moving from being celebrated, prestigious classical musicians but maybe feeling hollow inside, to having a deeply rooted authentic personal excavation.”

By the end, “Everything Rises” departs from the white-dominated space of the opening with the aim, Tines said, of “reclaiming agency.” He and Koh perform a duet about how they are connected, and how this project “allows us to see each other.”

“It’s about creating a new space,” Koh said. “And hopefully what we’re doing in this work will open space for people of color to tell more truth. It’s everybody’s loss, including classical music, if stories from people that are not like us are not heard.”

Copyright ©2022 The New York Time

© Jennifer Koh, All Rights Reserved. Photography by Juergen Frank. Site by ycArt design studio